日本木工小史

1. ─古代─ 木工の濫觴期(らんしょうき)

日本列島はアジア大陸の東縁に日本海を隔てて位置する南北に長い花綵[かさい]列島からなる。豊富な雨量と地味の肥えた土壌が相まって豊かな植生を誇る。はっきりとした四季は変化に富んだ木目を生み、錯綜する木理は複雑な杢を形成する。

高度に工業化の進んだ現代にあっても国土の約70パーセントは森林である。地球上には灼熱・酷寒にさらされ、いわゆる雑草も生えない土地が多い中、まことに幸福と言わねばならない。有用樹種も多く、現在、これほど多くの内外の樹種が木工用材として流通している国は他にはないだろう。こうして木材によるものづくり・木工は古来盛んである。

池のほとりの木杭が水面に接する部分のみ細くなってしまっているのをよく見かけるが、このように濡れた状態で空気に触れる環境が木には一番苦手だ。水や泥で酸素が遮断され腐朽菌の繁殖が抑えられた環境では意外と腐らない。鳥海山麓からは紀元前466年の山体崩壊で埋もれた杉の大木が神代杉として今日掘り出され工芸材料として珍重されていることでもわかる。しかし木工品となると完品の出土遺物は多くはない。鳥取県の青谷上寺地[あおやかみじち]遺跡などからも大量の木器が出土しているが、なんといっても雀居[ささい]遺跡(福岡市)出土の「組み立て式“案”[あん]」は指物の完成形を示唆して興味深い。“案”とは今でいう机のことだが、この遺跡からは泥水に浸かった状態でほぼ完品として出土している。板は最近の年輪年代学の知見により1世紀に伐採された杉であることがわかっている。「組み立て式」というが、今のキャンプ用品のように持ち運ぶために組み立て式にしたのではなく、接着剤などがない時代に木組みを維持するために楔などを用いて堅固に締結するためであり、結果として今我々は組み立て式と呼んでいるに過ぎないのではないだろうか。

木工品の嚆矢とも言うべき遺物だが、木工家の視点での研究はあまりされていないのが現状である。木工の実制作者と考古研究者との交流が進むことを期待したい。

2. ─奈良時代・正倉院─ 技術の完成

正倉院には数多くの木工の宝物が収められている。「国家珍宝帳」と呼ばれる献物品目録の筆頭は、仏教に深く帰依した聖武天皇の9領の袈裟であるが、その次に挙げられているのが「赤漆文欟木御厨子[せきしつぶんかんぼくおんずし]」である。この厨子は工芸史、木工技術史の2つの側面から重要な位置を占める。まずこの厨子そのものの来歴が注目される。天武天皇から聖武天皇までの天武系の天皇だけに6代に亘って伝えられ(途中天智系の元明天皇には伝えられていない)、いわば皇統を証明するかのような宝物である。

また技術的には、文欟木と呼ばれる杢の美しい欅[けやき]材を縦横に加工しこの大きなキャビネットを作り上げた技量に感嘆を禁じ得ない。当時は大型の鋸が存在せず、丸太を割って板や柱を作る割裂製材法に拠っていたといわれる。しかし果たしてこの厨子の複雑な杢の材を割って板にできるだろうか。私には不可能に思え、ある程度の大型鋸の存在を想定している。さらに扉には端喰[はしばみ]を施し、内部の棚板は蟻枘[ありほぞ]で組むなど高度な指物技法がすでに確立していたことがわかる。なかでも特筆すべきは支輪(葺き返し)の四隅の組み方である。この厨子は製作地の問題など未詳のことも多いが、1300年以上前から実在していたことは事実であり、その後の木工、特に指物の発展の基礎となったことは疑いない。

さらに奈良時代の木工史の大きなエピソードは「百万塔」の製作である。称徳天皇の発願で高さ20㎝あまりの檜製の塔が100万基作られた。膨大な数にもかかわらず寸法のばらつきがほとんどないことなど、日本の木工史上世界に誇る特筆すべき大プロジェクトである。

3. ─室町・桃山時代─ 茶道と木地の文化

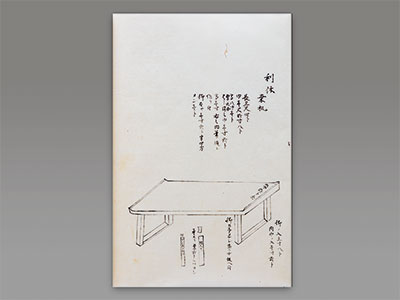

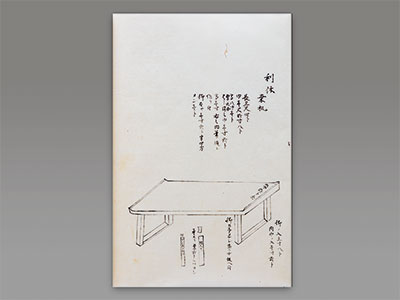

平安時代末期、栄西禅師によって宋からもたらされた喫茶の風習はその道具とともに「唐様の茶」として武家を中心に広まっていく。やがて室町時代となりその道具類は東山御物として文人的文化が花開くが、喫茶の風習そのものは村田珠光によって独自の道を歩むこととなる。珠光は中国からもたらされた漆塗りの台子の四本の柱を竹に変え、上下の板も木地のままの桐に変えた「竹台子[たけだいす]」を創案した。この棚は武野紹鴎[たけのじょうおう]、千利休と伝わり喫茶の習慣の和様化(=茶道)を象徴している。利休はさらに侘び茶を確立し現代に続く茶道の礎を築いたが、木地のままの木材を用いた棚物などを多く考案した。これこそ「侘び」の精神を象徴するものといえる。丸卓[まるじょく]は樽の鏡板を転用したともいわれるが、伝わる材料は素木[しらき]の代表、桐を用いて簡素な形ながら安定感のある形態である。また利休桑机は余分をそぎ落とした簡潔な形に凛とした高貴さを感じさせる文机である。さらに利休の教えを守った曾孫の江岑[こうしん]が考案した「三木町棚[みきまちだな]」は文字通り、杉、檜、樅[もみ]の3種を用い木工作品としても興味深い。素木を貴ぶ精神はその後の我が国の家具什器のあり方に大きく影響し「桐箪笥」「桑茶箪笥」などを生み出し木工芸の基本的精神となった。

4. ─江戸時代中期以降─ 木工の深化・普及

現在使われている桐箪笥[きりだんす]の原型は江戸中期以降に生まれたといわれる。箪笥を作ろうとして木取りした材料を重ねると、出来上がった箪笥の大きさ程度の嵩[かさ]になる。このように大量の木材を必要とする箪笥の誕生には、

1、規格化された材木の安定した流通、

山地での伐採技術の発展、運輸手段の確立。

2、指物技術の発展。

台鉋(室町時代に生まれたといわれ、現在の鉋と同形)の完成。

鋸[のこ]、鑿[のみ]などの道具鍛冶の出現、発展。

切れ味のよい道具があって精緻な組手などが可能。

3、何よりも経済的発展によって収納すべき身の回り品の増加、

所有への欲求。

などの要因がある。

こうして初めて箪笥などの家具調度の発達をみた。しかし実用品が多かったためか近世でありながら遺物は多くない。さらに他の工芸分野と比べて作り手の名前が残っていない。唯一の例外は松平不昧[ふまい]の恩寵を得た松江の小林如泥[じょでい]である。桐板に精緻な透かし模様を施した袖壁(東京国立博物館蔵)は糸鋸の無い時代にどのようにして作ったのか全くわからない。また板厚と同じ太さの釘を打った箱や組み立て式の酒器など高度な技を駆使しながらどこか遊び心のある作品を残した。一方全く同じ頃に東国の山間部(群馬県・東宮[ひがしみや]遺跡)で行われていた木工品が泥流の下から明らかになった。目的も精緻さも全く違う両者だが、どちらも指物の基本形を表している。木工技術の進化と地方における普及という面的広がりも示しており、同じ木工史の中で語られることが望まれる。

5. ─明治時代から戦前─ 木工藝の確立・御蔵島桑の発見と須田家3代

明治になり、江戸時代までの技術的蓄積の上に西洋からの近代的知見が加わり、木工技術は頂点を迎えた。近代的工芸としての木工芸確立の立役者、前田文之助桑明が日本橋東仲通りに工房を構える太田萬吉の下に弟子入りしたのが1882年(明治15年)である。太田は当時の国策であった工芸品輸出に深くかかわり海外の万博にも随行している。そのもとで修行に励んだ前田は出身地の三宅島や隣の御蔵島の桑に注目して本格的に使い始める。蒔絵などと違い御蔵島[みくらじま]桑の持つ華美ではなく剛健な美質は渋沢栄一など近代資本主義の推進者たちの禁欲的思想と合致し、彼らがパトロンとなり近代の美術としての木工芸の隆盛が始まる。前田桑明は、国内外の博覧会で受賞を重ね大正、昭和の二度の御大礼に御蔵島桑による指物が東京府からの献上品となり作家として地歩を固めた。作家名に「桑」を用いるほど縁が深い。祖父桑月がこの前田桑明の門を叩いたのは1907年(明治40年)、30歳の遅い再スタートである。しかし出身地岐阜県関市ですでに宮大工として出来上がっていた桑月はすぐに工房長となり、文字通り桑明の右腕となって支え、師の名前の半分をもらい「桑月」と名乗ることになる。ここから戦前、よき材料とよきパトロンに恵まれ桑月の桑指物師(桑物師)としての活躍が続く。昭和に入りその子桑翠がそれに加わった。須田家3代の木工芸の展開が始まった。

築地にあったころの東京府立工芸学校にて

6. ─戦後から現代─ 指物から木工藝へ

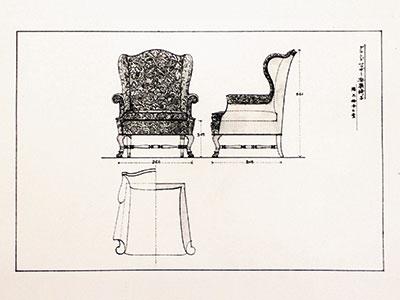

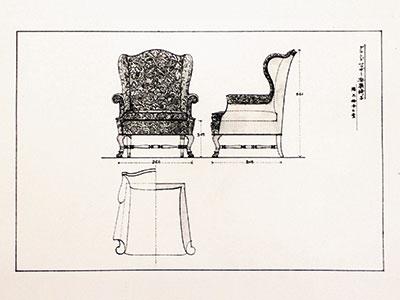

1945年(昭和20年)3月10日、道具やそれまで日本橋の工房にうずたかく積まれていた御蔵島桑の良材はこの東京大空襲で一晩にして灰燼に帰した。「御蔵島桑の時代は終わった。」父桑翠の述懐である。拠りどころとした材料も道具もさらにパトロンまでも失った桑翠はその持てる技術を最大に生かし、正統の仕事を続けるために戦後「工芸作家」の道を選んだ。自らが表現したいものを実現するために大学などで学ぶ西洋的、近代的方法に対し日本の工芸の展開にはこのように技術が先行する場合があった。手技が資本主義の発展の中で駆逐されず共存してきた日本の特徴だろう。ただ誰でも作家になりえるかといえば決してそうではない。桑翠の作家としての生き方とそれを裏付ける感覚は、師系に遡る太田萬吉、前田桑明、桑月そして何より本人の努力の賜物であることを強調したい。若くして茶道を良くし、さらに戦前から師事した梶田惠[かじためぐむ]の影響もまた大きい。梶田は芸大中退後舞台美術なども手掛けたが、留学経験がなく、情報の少ない時代にあって、中国、朝鮮、また西洋の各様式家具をよく咀嚼、設計し、製作指導に当たった。工芸にも造詣が深く、桑翠の仕事が指物から木工芸作品へと昇華する基礎を指導した。また桑翠は「木工芸の本命は家具だ」との梶田の教えを守り、棚物などにもよく取り組んだ。その発表の場が昭和29年に始まった日本伝統工芸展である。父桑翠が展覧会出品作と苦闘する様子を間近に見て育った私は第22回展から出品し始め現在に続いている。

A Short History of Japanese Woodwork

1. The Beginning of Woodwork — ancient times

From the beginning up to the present day, the history of woodwork in this country can be divided into several distinct epochs:

It is common to see wooden piles bordering the bank of a pond that seem to taper down to the area where they meet the water and this is because regular soaking and exposure to the air creates the worst possible environment for wood. However, if wood is fully submerged in water or mud, cutting off the supply of oxygen and thereby suppressing the propagation of decay fungus, then it is surprisingly resistant to rot. This can be seen from the fact that a huge cedar tree that was buried in a landslide at the foot of Mt. Chōkai in 466 B.C.E. has recently been excavated and is now highly sought after, as this kind of lignitised Japanese cedar is a material treasured by craftspeople. However, when it comes to examples of woodwork, very few archeological specimens have been discovered; a large number of wooden items dating back 2,200 to 1,700 years were discovered at the Aoyakamijichi site in Tottori Prefecture, but of particular interest is the ‘Collapsible Desk’ that was excavated from the Sasai site in Fukuoka City as this represents a complete example of cabinetmaking. Discovered completely submerged in muddy water, it is in virtually perfect condition and recent advances in tree-ring dating (dendrochronology) have shown that the timber used for the top board was felled during the first century C.E. Although today we refer to it as a ‘collapsible desk’, that is not to say it resembles today’s camping equipment that can be dismantled for easy transport, rather, as it was made at a time before the invention of glue, it was jointed together, then fixed in place using wedges, to create a sturdy structure.

This relic can truly be described as representing the roots of woodworking in Japan, but the fact is that it has received little research by people with a woodworking background and I look forward to a time when we see more interchange between archeologists and woodworkers.

2. The Perfection of Technique — 8th century / Shōsōin

The collection of the Shōsōin Repository dates back to the 8th century and contains numerous woodwork treasures. The Kokka Chinpō Chō [List of the Nation's Rare Treasures] is an inventory of all the items associated with Emperor Shōmu that comprise this collection and although the first entry is for nine Buddhist stoles that belonged to the Emperor, who had devoted his life to Buddhism, the next entry is for a ‘Red-lacquered Zelkova Cabinet’. This cabinet holds an important position in the history of both craft works and of woodworking technique. First, I would like to look at its provenance: it is said to have belonged to six Emperors of Emperor Tenmu’s line, from Tenmu to Shōmu, and so it can be said to have been a treasure that affirmed the Imperial lineage.

Made of zelkova timber with a beautiful grain that has been carefully worked to create the cabinet, we can only marvel at the skill that went into its construction. It is said that at the time it was made large saws did not exist and the only way to produce boards or columns was to use wedges to split large logs. However, would it really be possible to produce boards with a complicated grain such as those incorporated in this work simply by splitting? I personally think not and I can only presume that some kind of large saw did exist. Furthermore, if we look at the doors, we see that they have been finished using a clamp joint across the end of the grain while the internal shelves utilize dovetail joints, demonstrating that advanced woodworking techniques were already firmly established at this time. There are still many unanswered questions regarding this cabinet, such as where it was made, etc., but one thing we do know without doubt is that this kind of woodwork already existed 1,300 years ago and formed the basis for the development of future cabinetmaking.

Another important episode in woodworking history during the Nara period was the production of the ‘One Million Pagodas’. Empress Shōtoku, commanded the creation of one million pagodas, approximately twenty centimeters in height, but despite the huge numbers involved, there is virtually no variation in size among them. It was a vast project in woodworking history of which Japan can truly be proud.

3. Development of Tea Ceremony and Wood Culture — 14th to 16th centuries

The custom of drinking tea and its related utensils were introduced into Japan from China during the twelfth century by the Zen Master, Eisai, where it gradually spread among the samurai class. During the Muromachi period (1392–1573), the drinking of tea flourished as part of the literati culture, as can be seen in the Higashiyama Gyomotsu (The Art Collection of the Muromachi Shogunate), but it was not until the appearance of MURATA Jukō that a uniquely Japanese tea ceremony first began to develop. Jukō took the basic style of the lacquered utensil stand that had been imported from China and replaced the legs with bamboo while using plain paulownia wood for the upper and lower shelves to produce his ‘Bamboo daisu’ [shelf unit]. This stand was passed on to TAKENO-Jōō and SEN-no-Rikyū and can be said to symbolize the transformation of the tea ceremony from a Chinese to Japanese art. SEN-no-Rikyū is renowned for having established foundations of the wabicha style of tea ceremony that is still practiced to this day, and in addition, he also designed various shelves, etc., that highlight the natural beauty of wood. In fact it would be no exaggeration to say that these simple wooden implements symbolize the spirit of wabicha. The marujoku style of round utensil stand is thought to have originated from the lid of a barrel and is generally left in a plain wood finish, with paulownia being used to create a simple, yet stable form. The Rikyū Mulberry Desk has all unnecessary parts removed to produce a simple writing desk with a dignified, noble feel. Again, Rikyū’s great-grandson, Kōshin, who preserved Rikyū’s teachings, is known for his design of the ‘Mikimachidana’ shelves, which are interesting in that they consist of three different types of wood—Japanese cedar, cypress and fir. This spirit of reverence towards a plain wood finish was to have a powerful influence on the production of furniture and household fixtures in Japan, leading eventually to the appearance of paulownia chests-of-drawers and mulberry tea-cabinets.

4. The Refinement and Spread of Woodwork — 18th century onwards

The paulownia chests-of-drawers that are still common today are believed to have originated during the mid-Edo period and it is said that the amount of wood that can be obtained from a single tree is approximately the same as that required to make one chest-of-drawers. There three factors that led to the birth of these chests-of-drawers that require such a large quantity of wood: 1. The regular supply and distribution of a standardized timber through the development of logging techniques and the establishment of a nationwide transport system. 2. The development of cabinetmaking techniques, the invention of the hand plane (this is said to have first appeared during the Muromachi period [1392–1573] and resembled those used today), and the development of metalworking to produce saws and chisels. It was this appearance of sharp tools that made the development of elaborate joints possible. 3. Finally, and most important, was the development of the economy leading to an increase in the number of items requiring storage and a desire to possess more.

In this way, large numbers of chests-of-drawers and other kinds of furniture were produced, but being functional objects, not many remain today, despite their relatively late appearance. One notable exception is KOBAYASHI Jodei, a carpenter from Matsue in Shimane Prefecture, who received the patronage of the local lord, MATSUDAIRA Fumai. His ‘Side Screen in Paulownia’ (Tokyo National Museum) has a minutely detailed design in openwork that is an amazing achievement and it is a mystery how he achieved it in the days before the invention of the fretsaw. He also made a box using nails the same thickness as the wood and a sake cup that can be dismantled and reconstructed while remaining watertight, these works demonstrating his outstanding skill in addition to a sense of humor. In eastern Japan (Higashimiya, Gunma Prefecture), there is a village that was buried in a mudslide at around the same time that Jodei was active and various items of woodwork have been excavated from this site. The purpose of the works and the skill exhibited in their creation is quite different from Jodei’s work, but both demonstrate the same basic skills of cabinetmaking. From these we are able to learn more about the development of woodworking skills and their spread through the country.

5. The Establishment of Fine Woodwork, the Discovery of Mikurajima Mulberry, Three Generations of the Suda Family — Mid-19th century to World War II

With the Advent of the Meiji Period (1868–1912), Western Knowledge is Added to Japanese Traditional Skills and Woodwork Technique Reaches its Peak. In 1882, MAEDA Bunnosuke Sōmei, the man who was to go on to establish woodwork as a modern kōgei [art craft], was apprenticed to ŌTA Mankichi at his workshop in Nihonbashi Higashinakadōri. Ōta was closely involved in the government’s policy to boost exports of kōgei and visited various overseas expositions. For his part, Maeda was originally from Miyakejima Island and it was he who first started to use the outstanding mulberry timber that was available there and on the neighboring island of Mikurajima in his work. Unlike the lacquerware that had been popular prior to this, mikurajima mulberry possessed a more subdued, sturdy beauty that appealed to the abstemious tastes of SHIBUSAWA Eiichi and other leading advocates of modern capitalism who became his patrons, ushering in a period when fine woodwork would flourish as a form of modern art. MAEDA Sōmei received numerous awards at exhibitions both here and abroad, becoming famed for producing works in mikurajima mulberry that were presented by the Tokyo government at the coronations of both Emperor Taishō and Emperor Shōwa. So strong was his connection with mulberry timber, that he used the character for mulberry, ‘Sō’, in his name. My grandfather, Sōgetsu, did not begin to work for Maeda until 1907 when he was already thirty years old, which is quite late to start a new career, but when he was living in Seki City, Gifu Prefecture, he had mastered the skills of a temple carpenter and it was not long before he became manager of the workshop. He became Maeda’s right-hand man and eventually received half of his master’s name, adopting the name Sōgetsu. From that time until the prewar years he was blessed with a supply of good timber and generous patrons allowing him to work as a mulberry specialist cabinetmaker, known in Japanese as a kuwamonoshi. During the 1920s he was joined by his son, Sōsui, this marking the beginning of three generations of the Suda family being involved in fine woodwork.

6. Development from Cabinetmaking to Fine Woodwork — postwar years to the present

On March 10, 1945, the tools and the large stock of high-quality mikurajima mulberry timber that had been piled high in my father’s Nihonbashi workshop went up in smoke during the Great Tokyo Air Raid. As my father, Sōsui, later reminisced, this was the end of the mikurajima mulberry age. Having lost his materials, his tools and even his patrons, Sōsui chose to become a kōgei artist in order to carry on his traditional work while employing his skills to the full. Unlike the modern, Western model, where people study at university in order to learn how to realize their own expressions of creativity, Japanese kōgei places greater importance on technique. The fact that the skills required to work with the hands were not discarded during the Japanese industrial revolution but were able to coexist is probably unique to this country. However, that is not to say that just anybody can become an artist. I would like to stress that the reason why Sōsui possessed the skills and aesthetics required to become an artist in this way was due to his forerunners in this field—ŌTA Mankichi, MAEDA Sōmei and his father, Sōgetsu, but above all, it was the result of his own perseverance. When he was young, he began to study the tea ceremony and during the war, his teacher, KAJITA Megumu had a strong influence on him. After dropping out of the Tokyo University of the Arts, Kajita had done a variety of jobs including scenography, but despite never having been abroad to study and living in a time when such information was scarce, he had a wonderful understanding of Chinese, Korean and Western styles of furniture design, drawing up plans and offering instruction on their construction. He also possessed a deep knowledge of kōgei, and it was his instruction that allowed Sōsui to sublimate his work from cabinetmaking to fine woodwork. Sōsui also followed Kajita’s teachings in that he considered ‘the true essence of woodwork to be furniture’ and regularly devoted himself to the creation of shelves, etc., showing his work through the Japan Traditional Kōgei: Art Crafts Exhibition that was first held in 1954. While I was growing up, I often watched him struggling to complete works for this exhibition and I later joined him, first showing my work there in 1975, then subsequently every year to this day.